Alan Donovan Celebrating half a century in Africa with the arts

Published in The East African Nation media – 23 – 29 September 2017

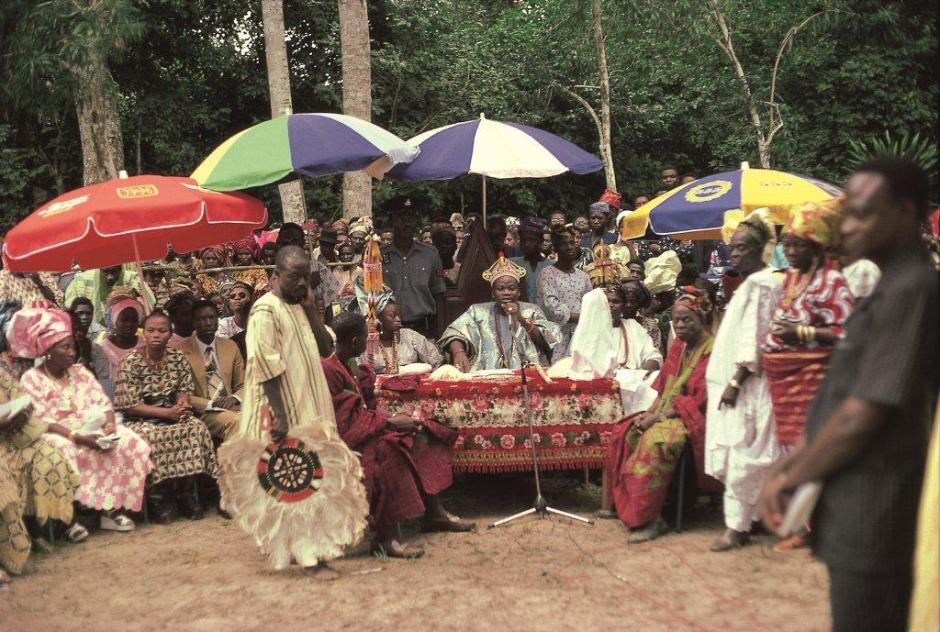

Above: Oshogbo King wearing beaded crown. Photo by Alan Donovan

It was in 1967 and the director of USAID in Nigeria was being installed as an honorary chief, riding on a white horse through the city of Oshogbo amidst pomp and glory – and in the crowd was Alan Donovan, young and recently posted to the country by the US government just before the devastating Biafra war broke out.

“It was a big transformation in my life,” recalls Donovan. “I was exposed to the wonderful traditional arts and textiles that they (the Nigerians) wove and dyed that are all endangered or nearly extinct now.”

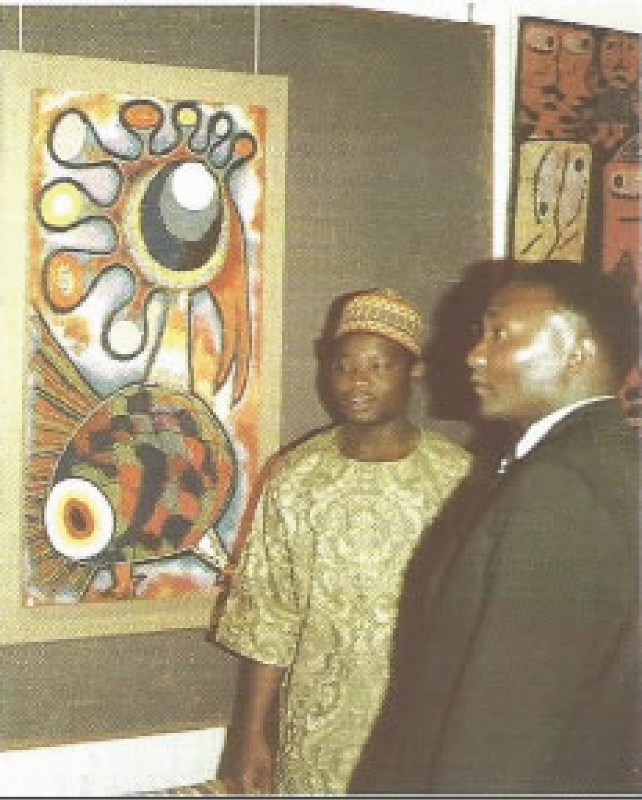

In the short stint before all hell broke loose – Donovan can recount horrific memories watching women fleeing with remains of their male relatives, body parts in baskets for burial – he had bought his first art work from one of the legendary Nigerian artists – Murama Oyelami.

He met many local artists in the town of Oshogbo of western Nigeria, where a cultural and artistic renaissance was taking place, inspired largely by three European artists.

Soon after, all foreigners were forced to leave Biafra, the breakaway former Eastern Regions of Nigeria, and it was Donovan’s first job to help evacuate them.

The Festival

To mark his 50 years in Africa, Donovan is putting up what may be his last extravaganza that was first seen in 1972 in Nairobi from the pioneering artists of Nigeria – largely from the town of Oshogbo. In 1971, Donovan had returned to Nigeria from his new home in Nairobi and travelled to each of the states in that country, collecting arts, textiles and artefacts before they vanished.

These were displayed at the First Nigerian Festival in Nairobi that he produced in January 1972 and which included a fashion show, the first in Nairobi with all African models, African textiles and African jewellery that morphed into Kenya’s African Heritage Festival that travelled the world with its troupe of models, dancers, acrobats, musicians and others.

The current Nigerian Festival will coincide with Nigeria’s National Day on 1st October when the event opens at the Nairobi Gallery housed in the century-old one-time Provincial Commissioner’s office.

“I have over 100 artworks, so this is one of the largest exhibitions of Nigerian art ever. It will be displayed in three locations the Nairobi Gallery, the National Museum and at the French Cultural Centre,” continues Donovan.

“Oshogbo Art will also be celebrating its 50 years and this collection of art from Nigeria is an archival collection that has been curated for me by Nike Seven Seven Okundaye, one of the continent’s foremost women artists, and only made possible because of the relationship I have had with the Oshogbo artists over the past 50 years.”

Also participating will be an acclaimed artist from Benin, Nigeria, Bruce Onobrakpeya, who participated in Donovan’s First Nigerian Festival in 1972 and then returned to Nairobi to open the new Pan African Gallery, the African Heritage, on Kenyatta Avenue in 1973.

The festival events at the Alliance Francaise will include an extensive exhibition of African textiles from the African Heritage House from 9-29 October, a return of the legendary “African Heritage Night” and the launch of the new album ‘Heart Of Africa’ by the phenomenal young musician ‘Papillon’ on 18th October and talks by Nike.

The Oshogbo Artists

In the 1960s the Oshogbo artists took the art world by storm. The artists were showing the world something so new and so un-influenced by the western world that it brought a wave of fresh air into the world of art. It was art by young Nigerians based on their Yoruba legends and folklore in mediums that were so expressive of their heritage.

“It was phenomenal,” states Donovan recalling his early days. “I fell in love with African arts and began looking for the masters that l’d seen in the art museums as a student.” Donovan studied international marketing, political science, journalism and as a side course African arts at UCLA. As a four-year-old, his first scrap book was on African animals cut out from magazines. “In those days we didn’t have TV.”

He talks about the late Twins Seven Seven – flamboyant and an actor – who started life as a ‘penny’ dancer invited to village performances, his performances based on legends and mythology of the Yoruba. He attracted the attention of Ulli Beier, a German studying African arts and culture in Nigeria. Beier was so captivated by Twin Seven Seven’s stories and characters that he asked if Seven Seven could draw them. And when he did, his work became legend. One of his first wives, Nike Seven Seven (now Okundaye) went on to become one of the continents foremost artists, famous for her batiks and other art forms,

It was the start of the Oshogbo art movement – started by three European artists –Ulli Beier, his first wife Susanne Wenger and then his second wife Georgina (after the divorce from Susanne). Wenger, an Austrian artist who first came to Nigeria in 1950 became so integrated into Yoruba life that she became the high priestess of the religious cult of OSUN, the goddess of water and fertility. She spent most of her life reconstructing neglected shrines and holy places in the town and along the banks of the Osun River that are now listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Georgina set up the first art school in Oshogbo in 1964, providing the materials and space where each artist went on to select his or her own niche – applique, cloth, metal, beads, tie and die, pen and ink worked on canvas, paper and wood – that became famous in the world’s art capitals.

Contemporary African Art

“If you look at contemporary African art, there is little to do with African heritage or truly things from their own heritage.”

And he defends his statement. “Nowadays, it’s global. There are some great Kenyan artists who have emerged but most of their arts are very similar to European artists.

“In the last three years, I have shown the pioneer contemporary artists of East Africa like Ancent Soi, Jak Katarikwe, Francis Nnaggenda, Expedito Mwebe, Elkana Ongesa, Sanaa Gateja and Lady Magdalene Odundo.

“Now we turn to the Pioneer artists of Nigeria who regularly exhibited at African Heritage.”

The Artists on Exhibition

Besides the famous print maker and innovator of many new artistic techniques, Bruce Onobrapeya, from the city of Benin, Nigeria, there is Jimoh Buraimoh, from Oshogbo, who first came to Nairobi with Donovan in l972 and who is internationally known for his pioneering use of glass beads mixed with oil paints, harking back to the beaded ceremonial items of the Yoruba;

Muraina Oyelami, from whom Donovan bought his first Nigerian art in 1967 and who started his career as a house painter, still uses a roller to layer his art. There are also Jacob Afolabi, the late Rufus Ogundele, and Adebisi Fambunmi who use strong black lines filled in with pastels or bright colours, all based on Yoruba mythology.

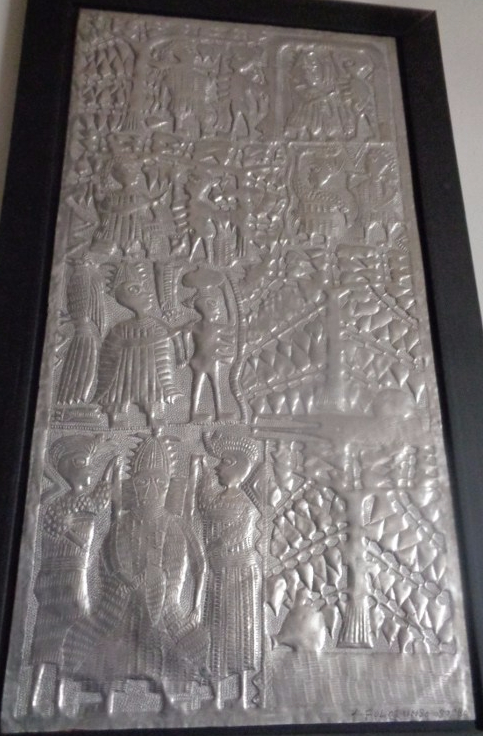

The oldest of these artists is the late Asiru Olatunde, a blacksmith, who rolled out panels of hammered metals based on Yoruba lore, and whose son, Folorunso, carried on his craft.

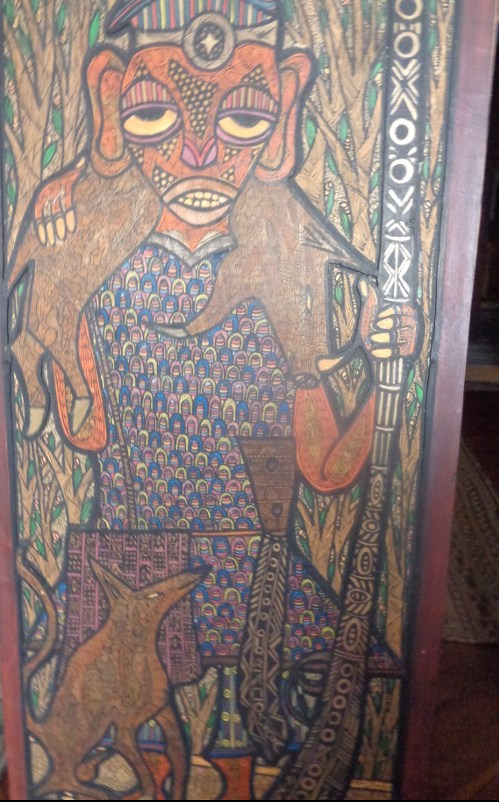

The most flamboyant of the artists is the late Twins Seven Seven (his odd name is because he was the sole survivor of seven sets of twins born to his Muslim father and Christian mother). He introduced his fanciful universe populated with spirits, bush ghosts and creatures centered round Yoruba legends, a spiritual, ghostly and invisible world inhabited by strange beings and imaginary creatures.

Twins was in big demand around the world not only for his fantastic fanciful universe but his dazzling personality. He died in 2011 and New York Times featured a long obituary on him. His imaginative style of art continues to influence artists.

Nike Seven Seven (now Okundaye,) one of Twins first wives, was brought up in traditional weaving and dying in Ogidi, Nigeria and rose to become acknowledged as one of the leading female artists of Africa. Nike has devoted her life to rehabilitating, preserving and restoring the textile heritage of the Yoruba, especially the ‘Adire’ (literally means to ‘tie and dye’) indigo dyed cloth. This cloth is wholly made by women, who paint the cloth with palm fronds or feathers dipped in cassava starch before dipping it in the rich blue-black indigo dye. The only work done on this cloth by men, is making stencils from zinc for some of the patterns, while others are done free hand.

Nike has given workshops on textile arts in many countries and her paintings are permanently displayed at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in the USA and in national collections of the UK. She will give lectures and appearances during the Festival.